A Thought About Aging I Can’t Unsee

We are not one organism.

☕🌴 Hi everyone, this is Andrii, and you are reading my brand-new newsletter, Molecules & Empires. You are reciving it because

In this newsletter, I’ll be sharing reflections on emerging ideas in science and technology — not as an end in themselves, but as a way to think about bigger things: how societies change, how power accumulates, and how certain futures quietly take shape. Molecules will show up sometimes, but mostly as a prerequisite for talking about something larger.

Some issues will be quite technical, others more generalist and strategic; some will be speculative and futuristic, others closer to the ground. We’ll see how it goes.

I’m still figuring out the exact shape of this newsletter, and I hope you’ll help shape it over time, through your feedback, replies, and conversations, which are very welcome!

For now, I thought I’d start with one idea that stuck with me after several recent conferences on aging research and drug discovery.

Anyway, off we go. Hope you enjoy it!

— Andrii

We are not one organism.

Roughly 70% of the human immune system sits in the gut, constantly interacting with trillions of microbes we do not control and rarely think about.

Yet for most of modern history, aging has been understood as something that happens to a single biological self.

Time passes. DNA accumulates damage. Cells become senescent. Chronic inflammation rises. Systems wear down. Eventually, things stop working as well as they once did.

This view is intuitive. It fits neatly with metaphors we already understand: clocks, entropy.

It also aligns with how medicine has traditionally approached aging: treat the organs, fix the parts, manage the failures.

But this assumption does more than shape explanations. It determines what kinds of interventions get built. If aging is something that happens inside a bounded organism, then medicine looks inward: repair DNA, clear senescent cells, tweak metabolism.

If that assumption is incomplete, however, then entire classes of interventions may be systematically undervalued or missed altogether.

Aging, in other words, may not be failing parts inside a machine.

It may be the gradual destabilization of a biological ecosystem.

You Are Not One Organism

The average human body contains roughly 30 trillion human cells.

But it also contains between 38 and 40 trillion microbial cells if we talk about an average 70 kg person.

These microbes — mostly bacteria, but also viruses, fungi, and other microorganisms — live on our skin, in our mouth, in our lungs, and most densely in our gut. Together, gut microbiota weigh approximately 0,2 kilograms, roughly the mass of a mango.

Interestingly: The microbiome is often said to weigh ~2 kg, but revised estimates put it closer to ~200 grams. The original overestimate came from assuming the entire gut had colon-level bacterial density; in reality, most microbes are confined to ~0.4 L of colon content, only part of which is bacterial mass.

The gut microbiome alone contains over 1,000 species of bacteria. Collectively, their genetic material outnumbers the human genome by a factor of about 150 to 1. In terms of raw biochemical activity, the microbiome is not a side system — it is a dominant one.

When functioning properly, this microbial ecosystem performs essential tasks:

Regulating immune responses

Breaking down nutrients we cannot digest ourselves

Producing signaling molecules and metabolites

Supporting tissue repair and metabolic balance

For most of our lives, we barely think about our own bacterial communities, and that may be precisely why their role in aging has been underestimated.

Balance, Not Presence, Is the Key

The microbiome is not inherently good or bad. What matters is balance.

A healthy microbiome is diverse, stable, and cooperative with its human host. When this balance is disrupted, a state known as dysbiosis, problems begin to emerge.

Dysbiosis can be triggered by many factors:

Chronic stress

Poor or highly processed diets

Repeated antibiotic use

Persistent infections

Environmental exposures

When microbial balance breaks down, harmful species can dominate, beneficial ones diminish, and the immune system is pushed into a constant state of low-grade activation.

This leads to chronic inflammation, one of the most consistent biological features of aging. But inflammation is only the beginning.

Dysbiosis and the Biology of Aging

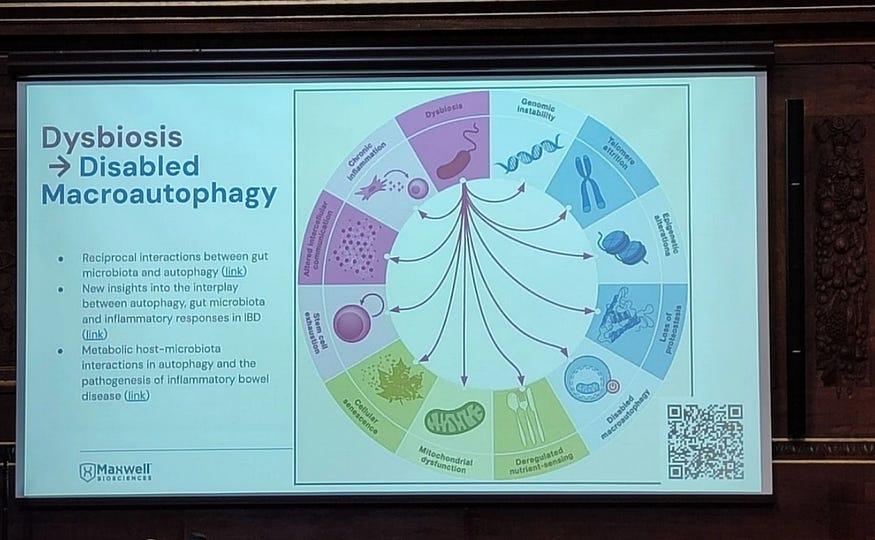

Modern aging research describes aging through a framework known as the hallmarks of aging. Originally proposed in 2013 and expanded in 2023, this framework identifies 12 core biological processes that drive aging across tissues and species.

They include:

Genomic instability

Telomere attrition

Epigenetic alterations

Mitochondrial dysfunction

Loss of proteostasis

Deregulated nutrient sensing

Cellular senescence

Stem cell exhaustion

Altered intercellular communication

Chronic inflammation

Immune system decline (immunosenescence)

Reduced tissue regeneration

It turns out, increasingly supported by evidence, that microbial imbalance influences nearly all of these processes. Chronic dysbiosis can:

Sustain inflammatory signaling that damages DNA

Accelerate immune exhaustion

Impair stem cell function and tissue repair

Disrupt nutrient-sensing pathways

Alter epigenetic regulation through microbial metabolites

At a major aging research conference, the Aging Research and Drug Discovery Meeting (ARDD 2024), which I attended in 2024 in Copenhagen, a CEO of a Texas, US-based biotech company, Maxwell Bioscience, Scotch McClure, presented this idea in what I found to be deliberately provocative terms.

He argued that aging should be understood, at least in part, as a communicable process, not because we “catch” aging from others, but because persistent pathogens and microbial imbalance act as upstream drivers of the aging process itself.

In his words:

“The human microbiome expresses over 200 times the human cell genetic expression. So the major lever in epigenetics is the microbiome. Therefore, aging should be at least partially treated as a communicable disease. Pathogens are a key driver of inflammaging, immunosenescence, stem cell depletion, heart disease, cancer, diabetes, and all-cause mortality.”

The claim, as I understand it, is not that microbes are the sole cause of aging, but that they may be a critical accelerator.

In this view, aging is not driven solely by the passage of time and the wear and tear of our bodies.

It is shaped by decades of biological interaction between human cells and the microbial environment with which they coexist.

Evidence From Cancer Research

This idea does not exist in isolation; for instance, in oncology, the role of the microbiome is already sound.

As I learned from a presentation by Rafik Fellague-Chebra, Global Medical Director at Novartis Oncology, during another event, the Drug Discovery Innovation Programme (DDIP) in Barcelona this year, clinical data show that antibiotic use can reduce the effectiveness of cancer immunotherapy by up to 50%.

In some cases, patients who do not respond to treatment regain responsiveness after receiving fecal microbiota transplants (FMTs) from patients who did respond.

This has led researchers to identify the oncobiome — the microbial ecosystem associated with tumors — as an active modulator of immune signaling, drug resistance, and cellular pathways such as mTOR and AKT.

The lesson is clear: microbes are not passive passengers, they shape biological outcomes at the highest level.

If they can determine whether advanced cancer therapies work, it is reasonable to ask whether they also influence how quickly bodies age.

Rethinking Intervention

If aging were purely mechanical, the solution would be mechanical: repair the damage, replace the parts, slow the clock.

But ecosystems do not respond well to brute force.

This is one reason why broad-spectrum antibiotics, while lifesaving in acute settings, are a poor long-term strategy. They destroy harmful microbes — but also beneficial ones. They destabilize microbial communities. And they drive resistance.

An ecological problem requires an ecological solution. But medicine is structurally better at repairing “individual machines” than ecosystems of organisms.

For clarity, ecological in this context is not about climate. In a broader sense, ecological = arising from interactions within a complex, multi-actor system, rather than from failures of individual components.

Anyway, clinical trials and regulatory pathways were built around interventions with a single, isolatable active ingredient and a relatively stable target, e.g. “block this receptor” or “replace this hormone.”

Microbiome-facing interventions collide with the opposite reality: massive baseline variability across individuals, feedback loops, and context dependence that make “one size fits all” harder to prove in a standard randomized trial design.

The incentives structure reinforces the same bias.

In many health systems, fee-for-service reimbursement rewards discrete, billable acts (visits, procedures, prescriptions) more reliably than long-horizon maintenance of complex risk factors, especially when benefits arrive years later and accrue to a different payer. In other words, we pay for repair more readily than we pay for ecological stewardship.

One emerging approach focuses on reinforcing innate immunity rather than eliminating microbes indiscriminately.

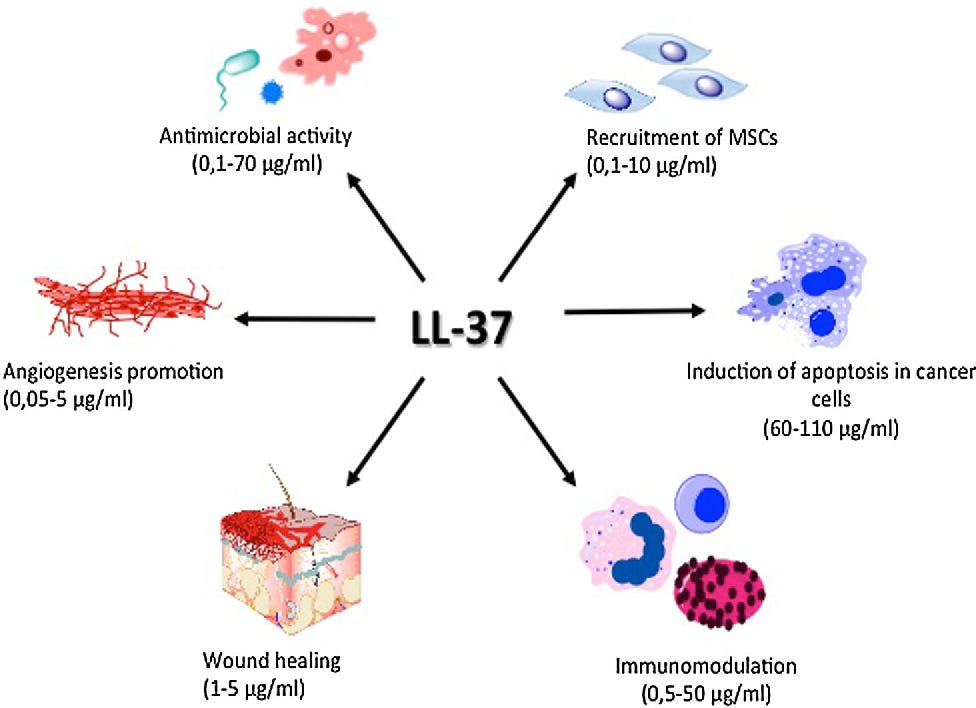

A case study is earlier mentioned biotech Maxwell Biosciences, which is developing synthetic analogs of LL-37, a naturally occurring antimicrobial peptide produced by the human immune system.

LL-37 is a remarkable molecule, and we all have it in our bodies!

It has broad activity against bacteria, viruses, and fungi, but in its natural form, it degrades too quickly to be used therapeutically.

Using a proprietary platform, the company created synthetic peptoids — chemically stable molecules that mimic LL-37’s function. These peptoids:

Are stable at room temperature

Do not require cold-chain storage

Show no resistance development in pathogen exposure studies

Do not disrupt healthy gut microbiota

Disrupt microbial membranes and biofilms while preserving host tissue

The lead candidate is delivered as a nasal spray, targeting the nasal–brain axis, a pathway increasingly implicated in inflammation and neurodegenerative disease.

The broader ambition, as I understand, is to create a synthetic immune system — modular, tunable molecules that restore immune balance, clear chronic pathogens, and reduce inflammatory burden without destabilizing microbial ecosystems.

The company plans its first clinical trials in 2026, with expansion into healthspan and aging applications.

Whether this specific approach succeeds remains uncertain. But the underlying logic is difficult to ignore.

A Different Story About Aging

Seen through this lens, aging is not simply decay, rather, it is the long-term outcome of coexistence with trillions of microbes. With environments — physical, social, and microbial — that gradually shape biological trajectories over decades.

It kinda changes what kind of problem aging is.

If aging is partly “ecological”, then it cannot be addressed only at the level of isolated organs or individual choices. It implicates food systems, public health infrastructure, infection control, living conditions, and the incentives that determine what kinds of interventions get built in the first place.

Some societies will learn to manage these ecosystems better than others. And the differences may compound slowly, invisibly, and profoundly.

Longevity, in this framing, is less about focusing on the body organs and tissues, but more about maintaining balance, biological, microbial, and institutional, under constant pressure.

In other words, we are not just bodies moving through time, we are environments embedded in larger environments.

And how well those environments are understood, governed, and maintained may shape not only how long we live, but who gets to age well.

To close this newsletter, here is a pretty entertaining (alarming, I should say?) article I think you may find interesting at any age:

Thanks for reading. Please share it with those who may find it useful!

— Andrii

You should read the research about chronic viral infections and neurodegenerative disease. For example heroesviruses and Alzheimer’s.